Duke Henry was irritated. A pious and religious man himself, he could not bear the sight of his beloved wife attending mass and performing all her noble deeds barefoot. She could be a shining example of both genuine and active faith, but she should not forget she was his duchess too. For the sake of her family and her own dignity she should present herself in more fitting attire. At least in public. But how to talk sense into that stubborn head of hers?

She wouldn’t listen to him. Long ago he had acknowledged who in their union had the last word. The only person he could turn to and whose words she would pay heed to was her confessor. Thus, the duke sought the latter’s cooperation. Everything went well, at least this is what the two conspirators thought. The duchess listened patiently, nodded her head in understanding, accepted a pair of brand-new shoes presented to her and solemnly promised to wear them. And she turned out to be as good as her word. She did wear them… tied to her belt. And this is how she has come down both in legend and history. Barefoot, with shoes dangling at her waist.

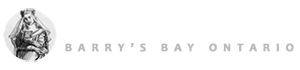

Duchess Hedwig with a pair of shoes tied to her belt and a model of Trzebnica sanctuary in her hand, c. 1370, National Museum of Wrocław. Photo courtesy of Tomasz Mizerka

Duchess Hedwig with a pair of shoes tied to her belt and a model of Trzebnica sanctuary in her hand, c. 1370, National Museum of Wrocław. Photo courtesy of Tomasz MizerkaThe future saint Hedwig was born sometime between 1174 and 1178 into a powerful Bavarian family. Her father was Berthold IV, duke of Merania, and her mother was Agnes of Rochlitz from the House of Wettin. The family was closely related to the ruling house of Germany, the Hohenstaufen. Through Hedwig’s sisters and their marriages, they also became related of the kings of France and Hungary. Hedwig herself received an excellent education at Kintzingen near Wurzburg. Not only could she read, write and interpret Holy Scriptures, but she learned what hard work meant and was not afraid of it.

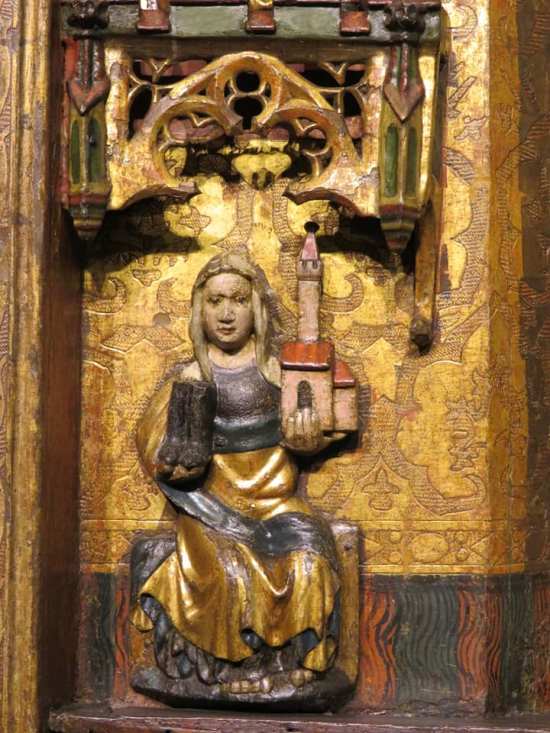

Count Bertold VI of Andechs-Meran and Agnes of Wettin, St Hedwig’s parents with their sons and daughters. Hedwig’s Codex, 1353. Wikimedia Commons

Count Bertold VI of Andechs-Meran and Agnes of Wettin, St Hedwig’s parents with their sons and daughters. Hedwig’s Codex, 1353. Wikimedia CommonsInitially she was to marry a ruler of Serbia, but when these plans came to naught her father arranged another match for her. This time he did not have to look far and in 1186, his daughter traveled to Silesia to the court of Frederick Barbarossa’s cousin, Duke Bolesław the Tall of the House of Piast. Hedwig brought to her future husband Henryk, Duke Bolesław’s son, not only a spectacular lineage and excellent connections, but also her own boundless energy which was to prove useful over nearly forty years of their marriage. If we are to believe the chronicler’s note, it was Hedwig who was to negotiate Henryk’s release when he was held captive by his political opponent. She walked barefoot and begged for his freedom on her knees until she gained what she came for.

Hedwig, Henryk and their children (from left to right): Gertruda, Agnieszka, Zofia, Konrad, Henryk and Bolesław. Hedwig’s Codex. Wikimedia Commons

Hedwig, Henryk and their children (from left to right): Gertruda, Agnieszka, Zofia, Konrad, Henryk and Bolesław. Hedwig’s Codex. Wikimedia CommonsHedwig and Henryk had seven children together, four sons and three daughters. In 1209 they decided to take a vow of chastity and keep it until they die. She was in her early thirties at the time, he was forty-three. Hedwig outlived her husband and four of their children. In 1241 she suffered a devastating blow when her beloved son Henry fell at the Battle of Legnica. Tradition states it was Hedwig, accompanied by her daughter-in-law, who identified Henry’s mutilated body at the battlefield. Reportedly, his death did not come as a surprise for she had seen it in a vision prior to the battle.

The aftermath of the Battle of Legnica. Henry the Pious head is paraded before the walls of the castle. Hedwig’ Codex, 1353. Wikimedia Commons

The aftermath of the Battle of Legnica. Henry the Pious head is paraded before the walls of the castle. Hedwig’ Codex, 1353. Wikimedia CommonsChildren were not the only ones she lost. Her sister Gertrude, queen of Hungary was secretly murdered and her other sister Agnes was exiled from her husband’s court and died in disgrace after the pope declared her marriage to King Philip II Augustus of France null and void and their children illegitimate. There is an air of sadness around the life of this youngest of Hedwig’s sisters.

Agnes was the first to die and was thus forgotten by her siblings. None of her brothers or sisters made any effort to preserve her memory. No donation was made for the sake of her soul, no necrology mentions her name. One reason for this was her uncertain status at the French court. Some did believe she was the king’s wife while others thought she was a mere concubine. Agnes was never crowned queen and thus her marriage proved not as prestigious as her father had hoped. Thus because of the surrounding scandal, her family must have thought it best to have her forgotten.

Agnes of Meran, the unfortunate queen of France and St Hedwig’s sister. Hedwig’s Codex, 1353. Wikimedia Commons

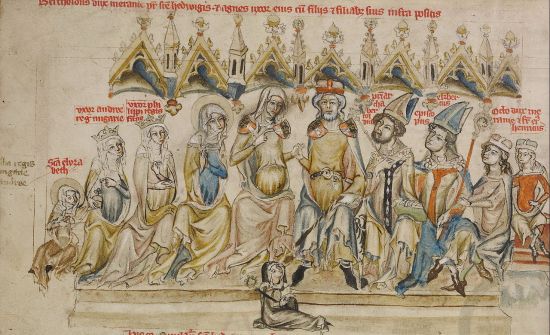

Agnes of Meran, the unfortunate queen of France and St Hedwig’s sister. Hedwig’s Codex, 1353. Wikimedia CommonsDespite personal losses Hedwig herself kept faith and continued to perform good deeds, taking care of the poor and ill, founding hospices and religious houses and introducing innovative methods while doing so. The convent of Trzebnica, for example, was built by criminals as the duchess thought it beneficial for them to replace their prison inactivity with hard work.

Her own life was one of prayer, hard work and self-sacrifice. She pushed herself to the limits of self-mortification with fasting, self-flagellation and hours spent in prayer. She departed this world on 15 October 1243 at Trzebnica. Shortly afterwards her resting place became a focus of miracles and a destination for pilgrims. She was canonized in 1267.

St Bartholomew crypt. The oldest surviving part of the religious house founded at Trzebnica by Hedwig and Henry. Photo courtesy of Witold Wiński

St Bartholomew crypt. The oldest surviving part of the religious house founded at Trzebnica by Hedwig and Henry. Photo courtesy of Witold WińskiHedwig is not only a patron saint of Silesia itself, but also of a great number of churches and towns. Her cult is still alive especially in her beloved Trzebnica, where following her wish her husband founded a religious house for nuns of the Cistercian order. Hedwig established close ties with it throughout her life, living, praying, working and dying there.

Hedwig convincing Henry to found the religious house at Trzebnica, today a sanctuary and her burial place. Hedwig’s Codex, 1353. Wikimedia Commons

Hedwig convincing Henry to found the religious house at Trzebnica, today a sanctuary and her burial place. Hedwig’s Codex, 1353. Wikimedia CommonsHedwig was also closely associated with the oldest surviving castle in Silesia. There are few signs of domestic comfort left at Wleń Castle today, but thanks to in-depth archaeological research we know where St. Hedwig must have dwelt and prayed during her frequent stays. The fortress continues to dominate the town and valley and from its walls we can admire the same breathtaking views the future saint admired in her day. Only last year, with great pomp and ceremony the tiny town of Wleń at the feet of the castle officially placed itself under her protection. Fond memories of the good duchess were evoked. These were her dower lands, after all, which she learned to love and care for. The citizens have not forgotten the duchess’s close ties with their town.

Wleń Castle – Its setting is among the most picturesque in both Silesia and Poland and its historic value unquestionable. This is where the future saint stayed. Photo courtesy of Anna Łasek, Wleń – Lahn Fotograficzne https://www.facebook.com/miastowlen (Przemysław Zatylny).

Wleń Castle – Its setting is among the most picturesque in both Silesia and Poland and its historic value unquestionable. This is where the future saint stayed. Photo courtesy of Anna Łasek, Wleń – Lahn Fotograficzne https://www.facebook.com/miastowlen (Przemysław Zatylny).

Further reading: “Women Rulers Throughout the Ages: An Illustrated Guide” by G. Jackson, “Princely Brothers and Sisters: The Sibling Bond in German Politics, 1100-1250” by J. Lyon, “Henryk Brodaty I jego czasy” by B. Zientara, Wleń Castle Official website